Of fan boys and soldiers - how ISIS perfected jihadist propaganda

© Fady AlGhorra and Mahmoud Elsobky

Bringing together the world’s foremost experts on on-line terrorism activity is never an easy task. Hacktivism and arts organisation Disruption Network Lab had to accomodate a security detail of several German policeman its Terror Feeds conference. We could not enter some sessions without having our bags checked. The attendeed were constantly being watched by guards.

The two rainy conference days in Berlin drew some 200 participants from universities, research institutes and law enforcement from around the globe, including Charlie Winter of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICRS) in London, Aaron Y. Zelin of research website Jihadology and Belgian researcher Pieter Van Ostaeyen of KU Leuven.

An alarming picture emerged.

The machinery of fear

Propaganda has always been one of the core activities of IS. Right from the start, the group’s communications were aimed at stirring up a wave of disgust and fear.

Via a businessman he came to know in the Syrian town of Manbij, al-Tamimi found a booklet titled ‘Principles in the administration of the Islamic State. The document described how the Islamic State was to be governed, how it would work administratively and how things like recruitment would be regulated.

The booklet also provided for the foundation of a set of central media organisations for the purposes of propaganda. ‘The document was no big master plan about how the Islamic State is structured, but it did show that media operations were baked into the organisation from the beginning’, says al-Tamimi.

From those beginnings in 2013 and 2014, ISIS developed a central organisation structure comprises a media council that reports directly to its leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi. ISIS also has an official spokesperson position in senior leadership. The most notorious of these was Taha Subhi Falaha, also known under his nom de guerre Abu Muhammad al-Adnani.

Caliphate declaration by al-Furqan Foundation

© Fady AlGhorra and Mahmoud Elsobky

‘One of the main misunderstandings about the ISIS caliphate is that is was announced by that famous video of the sermon of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in the al-Nuri mosque in Mosul’, says Pieter Van Ostaeyen. ‘That was not the case. It was in fact an audio message of al-Adnani a few days earlier that marked the start of the “caliphate”. This shows how important he was.’

Al-Adnani ’s audio was issued through the usual internet channels on 29 June 2014 and he brought out several other messages later. He was the one who, in the same year, called on potential terrorists worldwide to attack civilians in the West by any means possible, including low tech methods like knife and vehicle attacks.

That particular message was followed almost to the letter by dozens of radicalised young people committed terrorist attacks in Europe and the United States. We started analysing around 50 profiles of perpetrators of terrorist attacks in Western countries, from the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013 to the vehicle attack on pedestrians and cyclists in New York in October 2017.

Time and again we found that perpetrators of such attacks had consumed ISIS propaganda, including al-Adnani’s speech, or issues of the Dabiq and Rumiyah magazines containing ‘manuals’ for killing civilians.

Al-Adnani was killed himself in an airstrike in August 2016. But he left a professional propaganda machine behind which even today is inciting people to randomly commit mass murder.

Magazines and more

The audio and video messages from ISIS’ leadership are traditionally published via al-Furqan. That agency was already in operation in the days of Islamic State in Iraq and has traditionally been the main outlet for the big messages of the leadership of ISIS.

In addition, there are a number of other central media outlets like Al-Hayat Media Centre, which is known for its sleek video productions, including the extremely violent videos showing beheadings and executions, including the one of American journalist James Foley.

ISIS also runs a number of other central media organizations, such as the weekly al-Naba newspaper, the al-Bayan radio station, a media section that produces anasheed, islamist songs that often accompany the video and audio content.

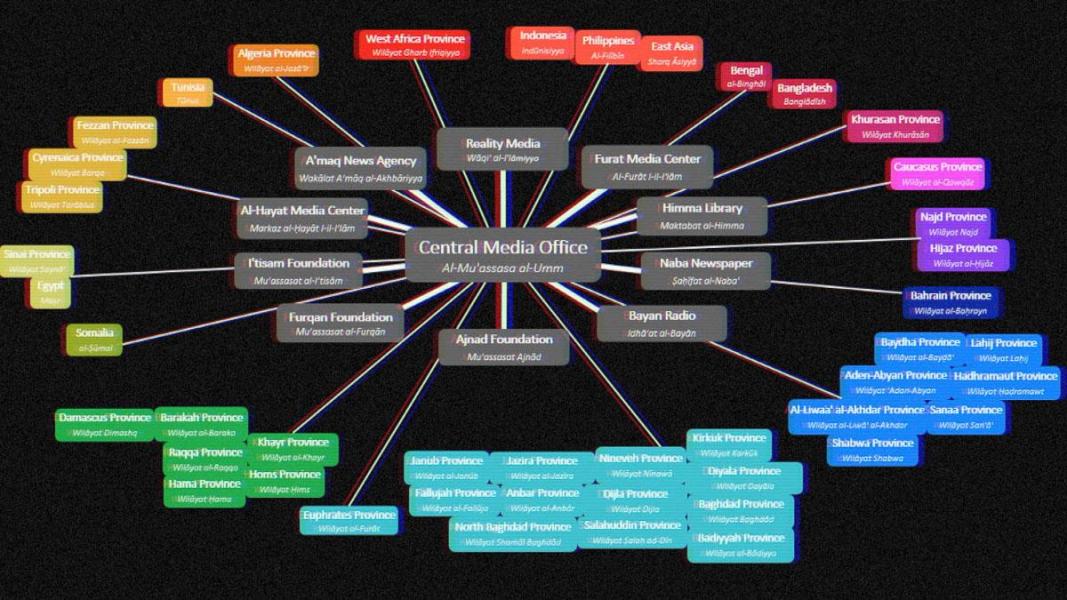

ISIS media strcuture, a diagram by Charlie Winter

© Fady AlGhorra and Mahmoud Elsobky

In addition to these central media outlets, ISIS operated several media outlets in its provinces or wilayat, which offered more localised content from regions in Iraq and Syria, and from other parts of the world where terrorist cells are operating under the guise of ISIS, such as the IS factions in Libya and Egypt, Boko Haram in Nigeria and terror groups in territories further afield such as Afghanistan and the Philippines.

Another key instrument in ISIS’ propaganda is the Amaq News Agency, a ‘non-official’ news outlet founded by Syrian ISIS sympathizer and self-declared journalist Baraa Kadek, who has since been killed in a US airstrike. Amaq came to prominence in Western media for publishing claims of terrorist attacks, including the Paris, Brussels and Nice attacks in 2015 and 2016.

Amaq tries to emulate the style and tone of a proper news media agency and publishes a lot of battlefield accounts and other ‘news items’, presented as factual information. It also avoids use of demeaning terminology to describe enemies or ‘non-believers’, which is much more pervasive in the core propaganda outlets of IS.

Fanboys

In Berlin, Charlie Winter presented research showing that at its peak in August 2015, ISIS churned out some 900 pieces of propaganda a week. In the early period after the “caliphate” declaration, ISIS mainly used Twitter as a means of spreading its propaganda over the world.

Social media allowed ISIS to get a lot of coverage, in large part thanks to some very technology savvy ISIS members running the official ISIS Twitter accounts and other outlets, and an army of so-called “ISIS fanboys”.

Charlie Winter

© Fady AlGhorra and Mahmoud Elsobky

Social media allowed ISIS to get a lot of coverage, in large part thanks to some very technology savvy ISIS members running the official ISIS Twitter accounts and other outlets, and an army of so-called ‘ISIS fanboys’ who helped copy and spread the videos, audio messages, magazines, anasheed hymns and other propaganda materials.

Other platforms like Google-owned Youtube and social media market leader Facebook were used as well. Jihadists never used them to the full, however, because they required much more detailed identification to create accounts. This made it harder for them to keep a flow of neww accounts going in case accounts were suspended, because it made creating new accounts more cumbersome.

In the meantime, a whole jihadist microcosm emerged, with thousands of accounts spreading the violent messages of ISIS, Al-Qaeda and other groups. ‘One user, Turjuman al-Asawirti, succeeded in creating some 1,400 Twitter accounts’, remembers Pieter Van Ostaeyen. ‘Every time he got suspended by Twitter, he immediately made a new account, sometimes three at a time.’

Mahmoud Elsobky (left) interviews “Bird”

© Fady AlGhorra and Mahmoud Elsobky

Bird

To get an insider’s view of ISIS’ propaganda machine, one of our producers tracked down a former ISIS member willing to talk. We headed to Istanbul, to one of the city’s densely packed neighbourhoods, and spoke to the young man for about an hour in a quiet little back room.

We’ll call him Bird.

Bird joined ISIS at the peak of its territorial expansion in Iraq and Syria. He was active as a fanboy, spreading ISIS propaganda on Facebook. He was soon contacted by an ISIS operative on-line and eventually made the journey to the self-styled caliphate where he, according to his own account, served as a soldier and was promised a position as a propaganda operative.

Bird was lured to travelling to the so-called caliphate because his handlers feared his prolific on-line campaigning would eventually put him at risk of discovery. The Internet Protocol number of the devices he used might have given his location away.

But, more importantly, Bird’s story shows how important waging ‘media war’ is for ISIS.

‘I watched a video of a girl that was arrested by the security services and badly sexually assaulted while police looked the other way. Wait I’ll show you…’

He started sharing ISIS content on social media out of frustration with the crackdown on Muslim Brotherhood protesters in Egypt during the revolution and the Rabaa sit-in massacre in 2013, when hundreds of supporters of ousted Muslim Brotherhood president Mohamed Morsi were gunned down during protests in Cairo.

Bird finally joined ISIS when he got word of on the internet of vicious attacks on female protesters by the Egyptian security services during the protests. ‘I watched a video of a girl that was arrested by the security services and badly sexually assaulted while police looked the other way. Wait I’ll show you…’

Bird grabs his phone and shows shocking footage. A chaotic scene in front of a red garage shutter, maybe a storefront. On the footage, policemen in battle dress are seen inside the building, a woman appears and puts her hijab back on and is being pushed around, apparently after having been assaulted by the policemen and others inside.

She gets pushed outside, through the gate, and is beaten by several men outside the gate. Other women try to help her and get kicked and trampled on too. The women plough themselves through the crowd, away from the fight. The footage does not show whether or not they escape the attackers.

Bird showing video of Egyptian female protesters being abused by police (September 2017)

© Fady AlGhorra and Mahmoud Elsobky

Bird soon got some traction on his social media accounts. He was then contacted by ISIS operatives on-line and got direct guidance on how to maximize the spread by creating new accounts every time an account is suspended.

‘All the outlets, like al-Furqan or Amaq have alternative channels of distribution as well’, says Bird. The branding of the propaganda is also strictly controlled by on-line operatives and each social media operative is enlisted with a specific media division of ISIS.

‘You may see fighters invading a military barracks, taking it, and then controllling the surrounding area. But in reality, it took them three months to reach that point, with 90 percent of the fighters killed before they even reached this target point.’

The Bird also shed some light on how ISIS operated its media inside territory under its control. New arrivals are strictly handled and have to hand in their mobile phones. Many get media training. Bird was forced to participate in a few battles. There, he saw first hand how the media machine works.

‘What you see in the propaganda videos is not necessarily what happened, they are often very heavily edited. You may see fighters invading a military barracks, taking it, and then controllling the surrounding area. But in reality, it took them three months to reach that point, with 90 percent of the fighters killed before they even reached this target point. So many of these purported big victories never happened.’

Bird’s account of ISIS’ military prowess shows just how manipulative the propaganda is. All the videos we found on Telegram showed nothing but military might. Bird’s story shows an entirely different side of the coin. He witnessed nothing but extremely high death rates of fighters as a result of airstrikes. ‘Many fighters also died because less skilled fighters shot them in the back accidentally as they were moving on the battlefield.’

Bird eventually got frustrated with ISIS because he did not get the position of media operative which was promised to him when he made his hijra, his emigration to the territorry of the self-styled ‘caliphate.’ He eventually left ISIS, risking his life in the process, as ISIS usually brutally cracks down on and kills those who are no longer loyal to the organisation. The deaths of ‘traitors’ are often prominently featured in ISIS’ video content.

Bird also points to the ‘false promises’ that were made to him as yet another way in which ISIS distorts reality for propaganda purposes.

© Fady AlGhorra and Mahmoud Elsobky

Who makes the videos?

Little is know about who exactly produces the videos, audio messages and other propaganda of ISIS, but it is clear that it is a very professional operation. ‘Media professionals joined ISIS, like photo journalists, journalists of opposition TV channels in Iraq and Syria’, said Bird ‘Many of them took their gear with them and started filming for ISIS.’

Through our own on-line research we found propaganda calling for media professionals to join the “caliphate”. Some clips show almost surreal scenes of a behind-the-camera director telling fighters how to stand and speak as the prepare to deliver a statement for a propaganda film.

Evidence emerging slowly from the dwindling “caliphate” seems to prove that the major battle and execution videos were shot in territory where ISIS can freely operate. Editing, post-production and dissemination seems to be a far less centralised affair, and may be done all over the world.

Many fighters also take cameras into battle. Bird spoke of children being sent into fighting areas as ‘scouts’, using mobile phones to film footage that may later end up in propaganda.

‘We cannot know for sure where, when and by whom these videos are made, but we can deduct a lot from the way it was shot, and the locations that were used’, says researcher Pieter Nanninga.

Evidence emerging slowly from the dwindling “caliphate” seems to prove that the major battle and execution videos were shot in territory where ISIS can freely operate. Editing, post-production and dissemination seems to be a far less centralised affair, and may be done all over the world.

There is also evidence, among other originating from former IS fighters like Bird, that ISIS propaganda operatives had a high status in the so-called caliphate, often earning far higher salaries than ordinary ‘grunts’ fighting ISIS’ wars, usually to be sacrificed in an endless barrage of suicide attacks in Iraq and Syria.

ISIS also spent a lot of money on propaganda. One document acquired by al-Tamimi showed that one month, IS spent 155,000 dollars on media in Deir Ezzor alone. Further documentation shows how different departments of ISIS would call in media operatives to cover their activities. ‘Many of the videos are of very high quality and look like Hollywood productions’, says Pieter Van Ostaeyen.

Some of the propaganda also clearly draws from internet and video game culture. References to the ultra-violent game Grand Theft Auto (GTA) are everywhere. ‘You had these videos where someone would mount a GoPro camera on the barrel of their Kalasnikov’, says Van Ostaeyen. ‘That would create very spectacular action footage, immersing the viewer into the battle. It’s a strange mix of youth culture with the ideology of something like Islamic State.’

Our own searches on Telegram yielded tons of such videogame-like material. In one clip fighters are sitting in a car, shooting at a van, while one of them says ‘why play GTA if you can do this stuff in real life??’

© Fady AlGhorra and Mahmoud Elsobky

Tool of acquiescence

With most of its territory in Iraq and Syria now gone, it has also become evident that ISIS used its propaganda inside the “caliphate” to install a regime of terror and to brutally squash any opposition that may have arisen in its territory.

‘You had these media points set up in each city under ISIS control’, says researcher Charlie Winter. ‘They would show propaganda videos and force people to watch.’ The graphic videos of executions would serve as a deterrent to those thinking of opposing ISIS. ‘It was a tool to acquiesce the local populations under ISIS control.’

‘You had these media points set up in each city under ISIS control. They would show propaganda videos and force people to watch.’

Syrian opposition media group Raqqa is being slaughtered silently (RBSS) documented these practices in great detail and tried to counter some of the narratives being imposed on local populations in ISIS-controlles areas, like ISIS’ Syrian ‘capital’ Raqqa.

RBSS sokesman Abdulaziz Alhamza explained how that worked when we spoke to him in Berlin. ‘They would spread loads of fake news and lies about the Shia or other populations, inciting hate in the locals. Many people fell for that narrative because they had no other information. So you can see how some people at least would start believing the propaganda.’

RBSS ran a small network of activists to counter those narratives inside ISIS-held Raqqa with media and hacking activities. They spreadfake versions of ISIS magazines, with the same cover so people could read them without causing suspicion. RBSS also carried out graffiti actions and they waged hacking wars with IS operatives.

It was extremely dangerous work. Some of the main activists, including family members of Alhamza, got caught and were brutally executed.

Some of those executions were made into propaganda videos by ISIS.

Hyper-active users

It remains very difficult to gauge exactly how big the world wide support base of ISIS and Al-Qaeda is. Attemps at making a tally based on social media use and propaganda yielded variable results, often with large margins of error. In our year of research, our team read through some 150 books, reserach reports, articles and other academic sources on the ‘cyber-jihad’. We found most results inconclusive.One thing did emerge from all the materials: the group of jihadi propagandists is probably very small, but extremely good at social media.

One often quoted report was a Twitter census of jihadi content by American think-tank Brookings Institution and Google in 2015, when ISIS was at the height of its influence.

‘Much of ISIS’s social media success can be attributed to a relatively small group of hyperactive users, numbering between 500 and 2,000 accounts, which tweet in concentrated bursts of high volume’

The researchers concluded that there were some 46,000 active ISIS-supporting accounts on the micro-blog website at that time. ‘Much of ISIS’s social media success can be attributed to a relatively small group of hyperactive users, numbering between 500 and 2,000 accounts, which tweet in concentrated bursts of high volume’, according to Brookings.

The Brookings census also showed that most of the propaganda was disseminated and consumed in the Arabic world. Three quarters of the content was posted trough Arabic Twitter accounts, with about a quarter on English speaking acounts, and smaller percentages in other languages.

Our own undercover research also showed that pattern of geographic distribution. Many fanboys were heavily involved in translations of propaganda, which is a common practice. Pieter Van Ostaeyen recalls being contacted at times by some of his on-line contacts to request translations.

A game of whack-a-mole

Since the heyday of the “caliphate” in 2014 and 2015, twitter has cracked down heavily on jihadi accounts. Thousands of ISIS and Al-Qaeda profiles were removed, and Facebook and YouTube / Google startde cracking down as well, which pushed IS-supporters to other platforms. These days Telegram, a heavily encrypted messaging app developed by Russian tech entrepreneur Pavel Durov, still offers a largely unpoliced space wher jihadists can operate relatively freely.

‘We focused too much on the acts of evil perpetrated by ISIS and we didn’t look at the deeper causes of the rise of this group.’

Pieter Nanninga

© Fady AlGhorra and Mahmoud Elsobky

Our year of undercover research also showed that this game of whack-a-mole between jihadists and internet companies is far from over. It remains exceedingly easy to get an anonymous SIM card somewhere and to use a smartphone to create a whole series of accounts and look for jihadis on Telegram, Paltalk and so many other platforms. It is simply impossible to gauge the size of this problem.

‘If one platform cracks down, they will simply move to another.’, says Pieter Nanninga. ‘Measures taken by large platforms like Twitter certainly had an effect, and the fact that a lot of jihadis are now on Telegram has diminished their reach compared to 2014 and 2015.

Yet IS and other terrorist groups keep popping up in headlines of news media. The propaganda never seems to miss its intended effect. Even now, with production of video’s and on-line magazines drastically reduced and the number of propagandists diminished by miltary actions agains IS and other groups, which killed several prominent propaganda operatives.

‘Maybe we paid a little bit too much attention to ISIS’, says Nanninga. ‘We focused too much on the acts of evil perpetrated by ISIS and we didn’t look at the deeper causes of the rise of this group. Now that IS has lost almost all of this territory, we should not sit back and think the problem is solved. ISIS is a symptom of a far larger constellation of problems marring the Middle East. And those problems have not been solved yet.’

This report was produced with support of the Fonds Pascal Decroos voor Bijzondere Journalistiek.

Maak MO* mee mogelijk.

Word proMO* net als 2798 andere lezers en maak MO* mee mogelijk. Zo blijven al onze verhalen gratis online beschikbaar voor iédereen.

Meer verhalen

-

Report

-

Report

-

Report

-

Interview

-

Analysis

-

Report

Oxfam België

Oxfam België Handicap International

Handicap International