Tom Claes is eindredacteur en journalist. Hij volgt de ontwikkelingen in de Hoorn van Afrika en focust in het bijzonder op de thema’s identiteit, conflict en ongelijkheid.

‘Everything that held us together as a people is now in ruins’

Children during a mourning ceremony for TDF soldiers.

© Pauline Niks

In November 2022, the Ethiopian government and the state of Tigray agreed to end two years of war. But how fragile is this peace? And what does the agreement mean for the population? MO* went there to find out. This is part 1: “Old friends, new enemies.”

“Nothing was spared,” says Rezene (pseudonym, real name known to the editor) with an uneasy grimace on his stubbled face. He glances at a broken piano and shakes his head.

Rezene is a guide and curator. The friendly thirty-something speaks in a controlled, soft voice. In late November 2020, he watched as national army tanks rolled into his hometown of Mekelle.

A few weeks earlier, on 4 November, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed had ordered his troops to bring order to Tigray. Like many other residents, Rezene and his family fled to safety. First in Mekelle, later outside the city.

The “brief military operation”, as the prime minister put it, was in response to an attack on a federal command post that he blamed on the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).

“This museum is a symbolic place. That is why it had to be demolished.”

But the operation would be anything but brief. For two years, the government army fought an unusually bloody war against the TPLF, or rather its armed wing, the Tigray Defence Forces (TDF).

The violence is estimated to have killed hundreds of thousands of civilians and left countless others cut off from food, communications and basic services. A peace agreement signed in Pretoria, South Africa, officially ended the bloodshed on 2 November 2022. But people are still suffering, and violence could flare up again at any time.

“After the Ethiopian soldiers took Mekelle, they used the museum as a command centre for eight months”, says Rezene. Traces of this are still visible throughout the building. Photographs, books and relics were destroyed. Empty tin cans and blackened cooking pots lie everywhere. Chairs and water barrels stand near the entrance. Next to them, on the floor, is a tangle of electrical cables. All sorts of clothes and bras draped over a wall also suggest the greatest of horrors.

“Look,” Rezene says. He points to slogans painted on walls and pillars, scathing texts mocking Tigrayans and the leaders of the TPLF. “This destruction is part of a campaign by the Ethiopian elite to wipe the Tigrayans off the map”, Rezene believes.

“This museum was about sacrifice, unity, education and cooperation. It was a powerful reminder of the importance of standing up for what you believe in and working together for a better future. It is a symbolic place. That is why the museum had to be demolished.”

Martyrs Memorial Museum in Mekelle (Tigray).

© Pauline Niks

Martyrs Memorial Museum in Mekelle (Tigray).

© Pauline Niks

Two rebel groups, two stories

Visibly affected by the destruction, Rezene leads us through the different halls. On the upper floor, he shows us a panel of black and white photographs. Groups of TPLF fighters meet and cook. Other pictures show young people being taught how to use a weapon.

These are scenes from the 1970s and 1980s. At the time, the TPLF was fighting a guerrilla war against the Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia, better known as the Derg.

When it was founded in 1975, the TPLF was little more than a group of rebellious students who wanted to address the structural backwardness of their region. It had no clear leader and no military experience. Moreover, especially in its early years, it was overshadowed by another rebel group: the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), led by the future president of Eritrea, Isaias Afewerki.

Despite fighting the same enemy, the two rebel groups differed in structure, military approach and vision. Eritrea was an Italian colony until 1941, when it came under British rule. It was annexed by Ethiopia in 1952, first as a federation and then as a province in 1962.

From the outset, the EPLF sought independence from Eritrea, while the TPLF sought more rights and political power in Ethiopia. It also wanted to include other ethnic groups.

Despite these differences, the two rebel groups would prove successful together. In the late 1980s, after numerous military defeats and the loss of important arsenals, the Derg forces were forced to withdraw from the rebel areas. On 28 May 1991, TPLF soldiers entered Addis Ababa, less than a week after the EPLF had liberated the Eritrean capital, Asmara.

Martyrs Memorial Museum in Mekelle (Tigray).

© Pauline Niks

Eritrea: a hopeful nation becomes a dictatorship

On 24 May 1993, the new flag was raised in Eritrea: the country was officially no longer part of Ethiopia. With Isaias Afewerki at the helm in Asmara and Meles Zenawi of the TPLF in Addis Ababa, the future looked hopeful.

But things started to go wrong in 1998. A border dispute over agricultural land around the town of Badme degenerated into a bloody war with trenches and tens of thousands of deaths on both sides.

“Eritrea was never big enough for Isaias Afewerki,” says Sarah Vaughan, an African history researcher and co-author of the new book Understanding Ethiopia’s Tigray war (2023). Even when tensions between the TPLF and EPLF rose in the 1990s, after Eritrean independence, Isaias still believed he could impose his will on Ethiopia.

During colonial rule, the Italians had turned the small country, strategically located on the Red Sea, into the industrial centre of Italian East Africa, which included Italian Somaliland (now Somalia) and Abyssinia (Ethiopia). They built theatres and Art Deco villas and paved picturesque alleys, parks and boulevards with coloured tiles.

Ironically, the colonial experience gave Eritreans a sense of superiority, Vaughan says. In their eyes, Eritrea was a bastion of culture and industrialisation. They looked down on the Tigrayans. These were “Agames,” day labourers who came to do odd jobs in Asmara, the sophisticated city with its great cafés, ice-cream parlours and fascist buildings.

In fact, says Vaughan, Isaias had the same attitude as the Italian coloniser: “Eritrea would get raw materials from Ethiopia, which it would process and export. This would be the basis of Eritrea’s prosperity. So when Isaias heard that the Tigrayans were starting to build their own factories, he was furious. He saw himself as the leader of the Horn of Africa, and certainly of Ethiopia.”

The 1998 border war was a sobering experience. The Ethiopian army was many times larger than the Eritrean one. Faced with a humiliating defeat in 2000, Isaias decided to take his chances and sign a fragile peace agreement. In practice, however, the conflict was not resolved and the border remained closed.

The military humiliation would change the Eritrean leader forever. He stifled criticism with harsh repression, and the press was irrevocably muzzled. The once-hopeful young nation was transformed into a dictatorship that sent its own subjects fleeing in unprecedented numbers.

Martyrs Memorial Museum in Mekelle (Tigray).

© Pauline Niks

Martyrs Memorial Museum in Mekelle (Tigray).

© Pauline Niks

Ethiopia: Tigrayans at the helm

In Addis Ababa, Meles Zenawi set out from the outset to break with the past and create a new, supposedly democratic society. A coalition government was formed with four parties from different ethnic backgrounds. On paper at least, all parties were guaranteed a high degree of autonomy, even the right to independence.

In practice, it turned out that the Tigrayans were calling the shots in the governing coalition. But the ethnic group makes up only 6-7% of Ethiopia’s 120 million people. This led to discontent, especially among the Amharic elite, who see themselves as the historical leaders of the country, and among the Oromos, who felt disadvantaged as the largest population group.

In 2018, the inauguration of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed brought to an end more than a quarter century of TPLF dominance, a period marked by economic growth, but also censorship and harsh repression.

“It was certainly not a fully inclusive or fully democratic period,” says Vaughan of Meles’s rule. But despite these shortcomings, there was great social and economic progress. Ethiopia made huge strides in reducing poverty. After his death, things went wrong.

With Abiy, the country seemed to be making a fresh start. He opened prison gates for journalists and political dissidents, lifted censorship, formed a government with half female ministers and promised to liberalise the economy. He also dissolved the ruling coalition and replaced it with a unity party, the Pan-Ethiopian Prosperity Party.

Most importantly, Abiy made peace with neighbouring Eritrea. This surprising move earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in autumn 2019.

But the euphoria was short-lived. Although the international community saw him as a conciliator, Abiy soon behaved like a divider at home. He spoke of “27 dark years under the previous government” and blamed the Tigrayans for everything that went wrong in Ethiopia. Not only the leaders of the TPLF were targeted, but the entire Tigrayan population.

Vaughan speaks of an “extremely cynical and potentially genocidal campaign by politicians who had little regard for the federal system and deliberately wanted to sow hatred.” They found an ally in the Eritrean regime. The Eritrean regime had always disliked the Tigrayan leadership because of its defeat in the border war. It was quite shocking for the TPFL and for many Tigrayans. They thought they were Ethiopians and discovered during the war that they were not.

“Everything was a target”

In their fight against the Tigrayans, the Ethiopian troops were supported by the Eritrean army and militias from the neighbouring Amhara region. These saw an opportunity to enforce old territorial claims by force. Numerically superior and backed by an arsenal of drones, the military alliance scored victory after victory.

“Every morning we could hear drones and planes flying overhead”, says a retired NGO worker in Mekelle. He stayed in the city as Ethiopian soldiers cleared the streets. “I could not leave because I would die without medication. I have hypertension, high blood pressure. But like food and water, medicine was hard to find.”

“My mother-in-law lived through three wars in her life, the last one broke her.”

The biggest worry, says the old man, was insecurity. “We lived in constant fear. You didn’t know when you were going to die. We were lucky that our house had a cellar. Whenever we heard planes or drones, we would hide there. Except for my mother-in-law. She stubbornly stayed in the living room every time. She lived through three wars in her life, the last one broke her.”

The man bats his eyes and rubs his hands uncomfortably. Then he sighs: “I don’t see any future for Tigray. Schools, hospitals and factories have been completely destroyed and looted. Valuable parts and raw materials were taken. Everything was a target in this war. Everything that held our people together is now in ruins. Even churches and mosques were not spared from the violence.”

© Pauline Niks

© Pauline Niks

Al-Nejashi Mosque

Near the town of Wukro, north of Mekelle, stands the Al-Nejashi Mosque. The iconic building dates from the seventh century and is said to be one of the oldest mosques in Africa. The minaret and dome were badly damaged by an impact. Some of the debris inside the building has still not been cleared.

The imam is absent, but his deputy tells how soldiers came to his village in search of Tigrayan fighters. According to the Ethiopian government, they were digging trenches around the mosque. “There was fighting in the area,” the man confirms, “but the Tigrayan fighters were nowhere near the mosque.”

He points to a bloodstain on the white marble. “Three young men were killed here. They had nothing to do with the army. One of them was a Muslim, the others were Christians. They hid in the mosque. Everyone was scared. There is a church nearby, but the mosque has an underground room.”

By then, more than half the village had fled. The imam’s deputy also sent his wife and children to a nearby town because Eritrean troops had destroyed their home. He stayed because he wanted to look after the mosque.

Today it is still in use. But the damage is extensive. “The Turkish ambassador to Ethiopia visited the mosque,” says the man. “He promised that Turkey would restore the building. This support is welcome because we can use every penny.”

Stalemate

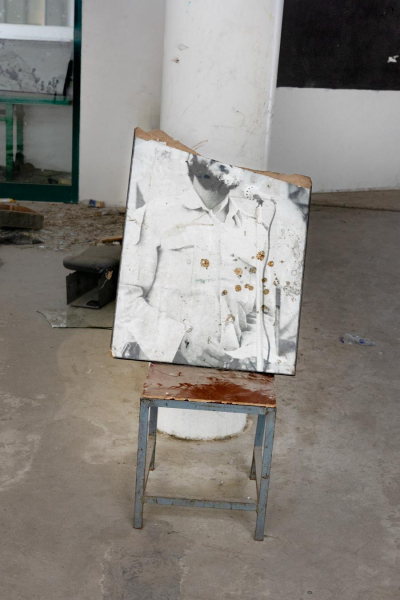

At the Martyrs’ Memorial Museum, curator Rezene sighs deeply. He looks at a portrait of Meles Zenawi and frowns. The battered painting sits on a wobbly chair. Part of the head of the Tigrayan resistance leader and former prime minister of Ethiopia has been cut off. As if part of the collective memory had been erased.

Portait of Meles Zenawi.

© Pauline Niks

“The museum pays tribute to our struggle against the Derg,” says Rezene. Photographs, drawings and infographs from the period have been brought together. The piano, captured by TPLF soldiers in the early 1980s and now smashed to pieces, was also given a prominent place.

“With this place, we wanted to preserve our history for future generations. We collected every penny from the Tigrayans for this museum. Even the peasants and people from the diaspora contributed.”

“We will completely rebuild the museum.”

In June 2021, Tigrayan forces regained control of Mekelle. A few months later, in November, they marched south, coming within 85 kilometres of the capital, Addis Ababa.

Foreign governments rushed to the aid of the Ethiopian government, particularly with drones. Eventually, the Ethiopian coalition pushed the Tigrayans back, and the momentum turned. A peace agreement was signed on 2 November 2022.

Like 40 years ago, every Tigrayan soldier during the war felt woyane, a resistance fighter. But today the cards are different, says Sarah Vaughan.

“It is one thing to lose your loved ones when you emerge victorious. But it is another thing to be defeated and then be told there is a peace deal, but not to have food for a year and not to have any support.”

But Rezene is not staying put. “We will completely rebuild the museum,” he says, sounding combative. “There will be a place for the martyrs who died in the last war. We may even build an additional hall.”

“Our history is far from being written. Whether that history will take place in Ethiopia is highly questionable.”

Maak MO* mee mogelijk.

Word proMO* net als 2798 andere lezers en maak MO* mee mogelijk. Zo blijven al onze verhalen gratis online beschikbaar voor iédereen.

Meer verhalen

-

Report

-

Report

-

Interview

-

Analysis

-

Report

-

Interview

Oxfam België

Oxfam België Handicap International

Handicap International